What Are Modern Us Veal Processors Doing To Improve Consumer Perception Of Animal Welfare

Abstract

At that place is widespread and growing concern among U.S. consumers about the treatment of farmed animals, and consumers are consequently paying attending to food product labels that indicate humane production practices. However, labels vary in their standards for animal welfare, and prior research suggests that consumers are confused by welfare-related labels: many shoppers cannot differentiate between labels that betoken changes in the way animals are raised and those that do non. We administered a survey to 1,000 American grocery shoppers to meliorate sympathise the extent to which consumers purchase and pay more for nutrient with sure labels based on an assumption of welfare improvement. Results showed that 86% of shoppers reported purchasing at least one production with the post-obit labels in the last year: "cage or crate-complimentary", "free-range", "pasture-raised", "natural", "organic", "no hormone", "no antibiotic", "no rBST", "humane", "vegetarian-fed", "grass-fed", "farm-raised". Of those who purchased one of the aforementioned labels, 89% did so because they idea the label indicated higher-welfare production practices, and 79% consciously paid more for the product with the label considering they thought that the label indicated better-than-standard animal welfare. However, many of these labels lack uniform standards for the production practices they represent, and some labels represent production practices that do not influence animal welfare, thus the degree of the animal welfare bear upon of a given label is highly variable. These results indicate that labels need to clearly and accurately specify their animal welfare benefits to meliorate the consumers' ability to buy products that align with their expectations.

Introduction

Research has demonstrated widespread and growing concern among U.S. consumers about the handling of farmed animals (Prickett et al. 2010). According to a recent national study, 78% of respondents reported being somewhat or very concerned nearly the welfare of animals being raised for food (Spain et al. 2018). Research has as well reported that almost one-half (49%) of respondents somewhat or strongly agreed that they consider the well-being of farm animals when making animal-sourced foods (ASF) purchase decisions (Prickett et al. 2010). At that place has also been a consequent increment in the past several years in the number of U.Due south. consumers who prefer eggs, meat, and dairy products from higher-welfare production systems (Holger et al. 2008; Janssen et al. 2016; Lusk et al. 2007) and are willing to pay more for eggs, meat, and dairy products that come from humanely treated animals (Heng et al. 2016; Janssen et al. 2016; Lusk et al. 2007; Ortega & Wolf 2018).

Because consumers generally cannot observe production practices, they rely upon labels for this information. Indeed, consumers are paying attention to food product labels that indicate humane production practices (Spain et al. 2018). While many labels communicate about animal welfare attributes, not all labels have consistent and required standards, and the degree of improvement to animals' lives can vary by both label and the type of animate being product bearing a given label. In many cases, the company may create its own standard confronting which they are measured (FSIS - USDA 2019; Sullivan 2013a), thus whatsoever improvements in animal welfare vary substantially within a given label. In other cases, labels practice non represent any comeback in animal welfare, despite consumers' assumptions that they practice. These conditions can lead to consumer confusion about which labels correspond improvements in animal welfare over a conventional product, and to what extent.

Our aim with this research was to depict U.S. consumers' use of labels to identify improvements in animal welfare over a conventional product. We captured this by collecting data on the proportion of consumers who both purchased and paid more for products with labels because they idea the characterization indicated higher-welfare production practices. This information helps usa to better understand if and how the current label scheme provides sufficient information to consumers about animal welfare and the extent to which there is a disconnect betwixt consumers' expectations of the animal welfare benefit of a label and the welfare do good the characterization renders.

A survey was administered to 1,000 U.Southward. grocery shoppers, aimed at attaining information almost consumers' past-year purchases of ASF with welfare-related labels and what portion of those consumers made those purchases because they thought the label ensured higher-welfare product practices. We asked respondents whether they purchased a product with this label, whether they purchased that product because they idea the label indicated higher-welfare production practices, and whether they knowingly paid more for the production with the label because they thought it indicated college-welfare production practices. Additionally, we analyzed to what extent these same consumers purchased products with animal welfare certifications that stand for consequent and measurable higher-welfare production practices because they take established standards and are verified by third-political party audits.

Background from Past Inquiry

In general, labels communicate information about products to consumers, some of which are unobservable attributes such as production processes (Darby & Karni 1973). The increasing distance between ASF (animal-sourced food) production and consumption causes consumers to rely heavily on labels to inform food purchasing decisions (Hepting et al. 2014). However, the information provided through a characterization can be express and consumers may make inaccurate assumptions nearly what that characterization represents (Abrams et al. 2010; Kuchler et al. 2020). For instance, many consumers inaccurately equate the "natural" label with no antibiotics or hormones and/or the use of organic product practices (Abrams et al. 2010; Kuchler et al. 2020).

Some other reason for this gap is consumers' lack of understanding of modern farming practices and how they impact welfare (Harper & Makatouni 2002). For instance, consumers underestimate the proportion of eggs produced from hens in battery cages (Norwood & Lusk 2011; Prickett et al. 2010), and wrongly assume that broiler (meat-blazon) chickens are raised in cages versus cage-free (Lusk 2018). Consumers also inaccurately assume that hormones are frequently used in egg, craven, and turkey production and are willing to pay more for the hormone-complimentary label despite the fact that federal regulations prohibit the use of hormones in these products' production (Yang et al. 2017).

Welfare benefits of a given label as well vary based on the product blazon and consumers cannot distinguish between products that behave the same label but represent different animal welfare benefits for dissimilar ASF products (Sullivan 2013b). For instance, the "cage-gratuitous" label on chicken indicates no additional allowances because broiler chickens are not typically raised in cages in the U.S. Conversely, eggs labeled "muzzle-free" were produced by layers not confined to cages, which is an improvement from the standard exercise of confining multiple hens to pocket-size "battery" cages (Lusk 2018).

Another source of misunderstanding arises from inconsistent animate being welfare standards or enforcement mechanisms for labels. For example, companies and producers tin can label ASF as "humane" based upon their own definitions of humane production practices, which may be no dissimilar from standard production practices (FSIS - USDA 2019). Likewise, outdoor access requirements for the "free-range" label are unspecified and have no minimum space requirements (FSIS - USDA 2019); therefore, the quality and duration of outdoor admission may vary dramatically across farms.

Effigy i provides the standards required for label apply, the managing authorization, and the welfare implications of the subset of labels focused on in this report. In the cases of "muzzle-complimentary" on meat birds, "crate-free", "farm-raised", and "humane/humanely-raised", at that place is no official standard defined by the USDA; producers gear up their own definitions and share documentation with the USDA Food Condom and Inspection Service (FSIS) which verifies adherence to this standard through the label pre-approval process on a case-past-case basis (FSIS - USDA 2019). There is no on-farm inspect required to employ these labels.

For other labels, standards are gear up for the utilise of the characterization on some production types merely not others, so the impact of the label varies based on the product upon which it appears. In the case of "natural", the USDA standards apply to meat and poultry, and require that (1) the product does not contain any artificial flavor or flavoring, coloring ingredient, or chemic preservative, or whatever other artificial or synthetic ingredient; and (2) the production and its ingredients are not more than than minimally processed (neither of which impact animal welfare). Nonetheless, in that location is no such definition for the apply of the "natural" label on eggs and dairy, but it is still used. Similarly, the "no hormone" label is regulated by the USDA, however, hormones are legally prohibited from employ on chickens and turkeys, thus the label only represents a change in product practices for pork, dairy, and beef cattle.

For other labels, there are limited standards required to apply the label, and so over again the welfare impact varies broadly. For the use of the "costless-range" label on poultry and beef, the USDA establishes some standards simply does not specify the size, duration, or quality of the outdoor space which means conditions will vary dramatically between farms (as will the welfare touch). Similarly for the apply of the "muzzle-gratuitous" characterization on eggs, while hens cannot be bars to cages, the guidance falls short of defining infinite and outdoor access requirements. Every bit a result, conditions for these animals vary broadly by farm.

Of the labels included in this study, only one, "organic," has brute welfare standards that are both broadly defined and enforced. Organic is a federally regulated program with measurable, publicly available standards that are audited on-farm regularly. The USDA definition of "organic" requires animals to have continuous access to pasture yr-circular, which likely ensures that the animals have spent some portion of their lives outdoors, which has inherent welfare benefits over continual confinement. However, "access" is not clearly defined (due east.g. number of access points, amount, or quality of pasture), therefore animals may notwithstanding be confined in high densities (USDA Agricultural Marketing Services 2017).

Materials and Methods

Survey

To amend empathize if the current label scheme effectively communicates information near creature welfare to consumers we utilized a cantankerous-exclusive survey to decide the proportion of U.South. consumers who purchased and paid more for ASF products with a given label considering of their expectation that it represents higher-welfare product practices. Nosotros, in collaboration with Lake Enquiry Partners, surveyed 1000 U.Due south. consumers of beast-sourced foods (ASF: meat, eggs, and dairy products) from January xv–23, 2020 to identify purchasing and perceptions of ASF product labels. Survey respondents included members of consumer panels who previously volunteered to participate in market place research. Participants were emailed an invitation to consummate an internet-based survey. Respondents eligible for the survey were U.S. residents 18 years onetime and older who indicated that they were the master or co-primary grocery shopper of the household and had purchased at least some ASF for their households in the last twelvemonth.

The survey consisted of questions well-nigh consumers' level of concern about the welfare of animals raised for nutrient, whether they purchase ASF products with welfare-related labels, whether they purchase ASF products with welfare-related third-party certification, if they would switch to an ASF product with a certification that guaranteed a higher animal welfare standard, and their desire for regime regulations surrounding animal welfare food labeling (Encounter Supplemental Materials for the full survey). To reduce the likelihood of preferentially selecting respondents with positive attitudes towards animal welfare, the survey invitation did not mention brute welfare and instead indicated that the topic was "issues that people have been discussing recently well-nigh food, eating, and shopping habits," and no questions related to animal welfare were provided until after the respondent was determined to be eligible for the study.

To ensure the sample population represented the population of national shoppers, responses were weighted slightly past gender, age, region, race, political party identification, and pedagogy. Survey question responses with four or more categories were collapsed into two categories to facilitate analysis. For instance, responses "very probable" and "somewhat likely" were combined equally "likely," and "not very likely" and "not at all likely" were combined every bit "unlikely". Responses were summarized as proportions with exact 95% conviction intervals for binomial proportions using the Clopper-Pearson method. All statistical analyses were conducted in Stata (StataCorp. 2017. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC).

Labels

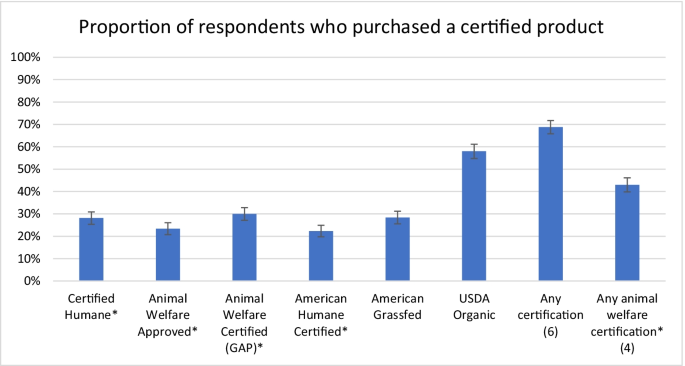

Respondents were asked nigh past 12-month purchasing of the following labels: "cage or crate-free", "costless-range", "pasture-raised", "natural", "organic", "no hormone", "no antibiotic", "no rBST", "humane", "vegetarian-fed", "grass-fed", and "farm-raised". Consumers were as well asked if they were currently buying ASF with the following certifications: Certified Humane, Animal Welfare Approved, Creature Welfare Certified (GAP), American Humane Certified, American Grassfed Association, and USDA Organic (Fig. 2). These certifications vary in their requirements and the types of farming systems they allow, only in dissimilarity to the claims listed above, these programs each have multi-pronged, publicly-bachelor standards which include prohibitions on common, conventional practices that bear on animals' welfare, regular on-farm audits, and enforcement of standards.

Certifications included in the survey

Results

More than three-fourths of our sample (76%) of consumers reported that they were the primary grocery shopper, and the remaining 24% reported they shared equal grocery shopping responsibility in their household. This sample generally reflects the characteristics of household grocery shoppers published elsewhere (Ortega & Wolf 2018; Kingdom of spain et al. 2018) (Table ane). Compared with the general U.South. population, this weighted sample had slightly more females than males and more households with children. This sample was likewise older, with more education and lower-income than the general U.S. population.

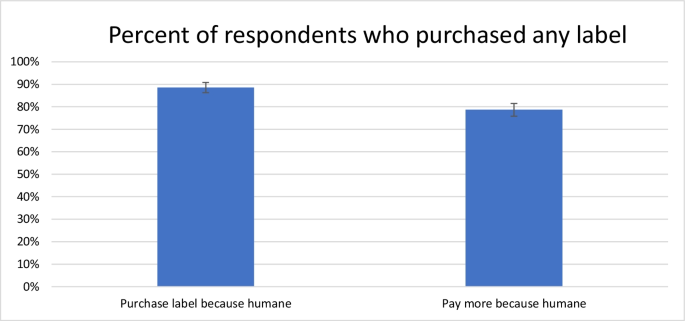

Ninety-six percent (CI 94–97%) of respondents reported purchasing meat, 95% (CI 93–96%) reported purchasing eggs, and 96% (CI 95–98%) reported purchasing dairy at to the lowest degree once per calendar month in the last twelvemonth. Seventy-six pct (CI 73–78%) of respondents reported they were somewhat or very concerned about animal welfare. Fourscore-six pct (CI 84–89%) reported purchasing at least 1 of the following labels in the last twelvemonth: "cage or crate-free", "complimentary-range", "pasture-raised", "natural", "organic", "no hormone", "no antibody", "no rBST", "humane", "vegetarian-fed", "grass-fed", and "farm-raised". Of those who purchased one of the same labels, 89% (CI 86–91%) did and then considering they thought the characterization indicated higher-welfare production practices, and 79% (CI 76–82%) consciously paid more than for the characterization because they thought that the label indicated college-welfare production practices (Fig. 3). Sixty-9 percent (CI 65–72%) reported purchasing a 3rd-party certified egg, meat, or dairy production, and 43% (CI twoscore–46%) reported purchasing egg, meat, or dairy products with a tertiary-party certification specifying animal welfare in the label (Certified Humane, Animal Welfare Approved, Animal Welfare Certified (GAP), American Humane Certified). Lxxx-three pct (CI 80–85%) of respondents reported they would be probable to switch to a meat, egg, or dairy brand that guaranteed that the products came from farm animals raised under higher animate being welfare standards. Eighty-five percent of respondents (CI 82–87%) reported that they idea the government should exist setting and enforcing clear definitions for nutrient labels related to animal welfare.

Percent who purchased or paid more than for welfare label because they believed it indicated college-welfare production practices

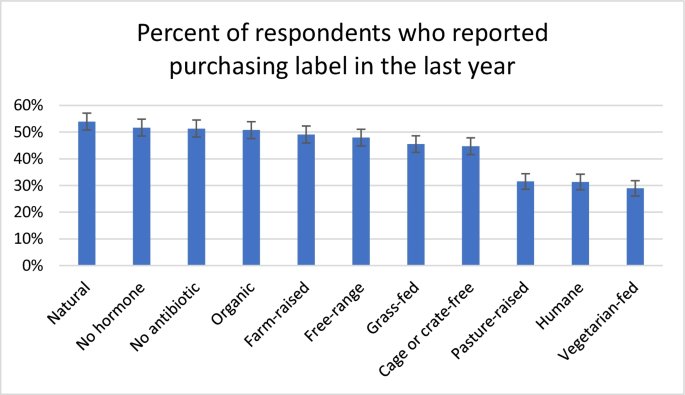

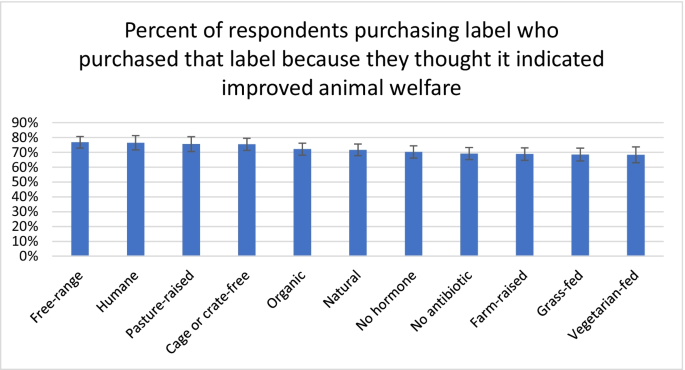

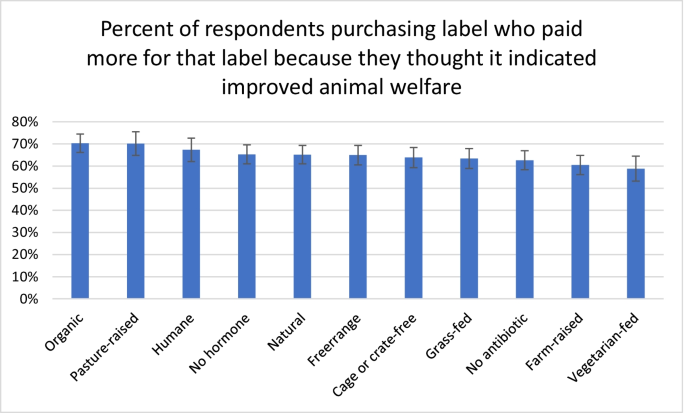

The proportion of respondents who purchased a given characterization varied beyond labels (Fig. iv); 29% reported that they purchased the vegetarian-fed label and as many as 54% purchased the "natural" characterization. The vast majority of consumers reported they purchased a given label because they thought that label indicated higher-welfare product practices (Fig. v) and reported paying more than for a given label because they idea the label indicated higher-welfare production practices (Fig. half-dozen).

Percent of respondents who reported purchasing a given characterization in the last year, past label

Pct of purchasers who purchased because they believed label indicated higher-welfare product practices, past label

Percent of purchasers who paid more because they believed label higher-welfare production practices, by characterization

Because of variation in the availability, meaning, and regulation of labels across product types, nosotros disaggregated the percent of individuals who reported purchasing a given label across labels and ASF production type (Appendix Tabular array five), the percent of individuals who reported purchasing a label considering they thought the label indicated higher-welfare production practices (Table 2), and the percentage of individuals who reported paying more than for a label because they idea the characterization indicated higher-welfare production practices (Table 3). Beyond all labels and product types, near consumers who reported purchasing a specific characterization did so with the intention of purchasing a college welfare product (Tabular array iii). In some cases, such equally "organic" chicken, "humane" dairy, and "pasture-raised" eggs, at least 3-quarters of consumers purchasing those labels did and so considering they thought that label indicated higher-welfare production practices.

Figure 7 shows the proportion of respondents who reported that they purchased meat, egg, or dairy products with one of the six certification labels: Certified Humane, Beast Welfare Approved, Animal Welfare Certified (GAP), American Humane Certified, American Grassfed Association, or USDA Organic. Sixty-nine percent (CI 66–72%) of respondents reported purchasing at least one of the 6 certifications, and 43% (CI 40–46%) reported purchasing one or more of the iv certifications that specify college-welfare production practices: Certified Humane, Animal Welfare Canonical, Animal Welfare Certified (GAP), American Humane Certified.

Proportion of respondents who reported purchasing a certified meat, egg, or dairy product, by certification

Several certification labels incorporate terms that are likewise used in generic labels. "Certified Humane" and "American Humane Certified" contain the term "humane"; "USDA Organic" contains the term "organic"; "American Grassfed Clan" contains the term "grass-fed." To identify the extent to which consumers purchase third-party certifications and also generic labels that exercise not adhere to the same standards, we calculated the proportion of respondents who reported purchasing a broader, generic characterization as a proportion of those purchasing the certified label. Of those who reported purchasing the "grass-fed" label, 42% (CI 38–47%) as well reported that they purchase ASF products with the "American Grassfed Association" certification. Of those who reported purchasing a "humane" or "humanely-raised" characterization, 53% (CI 47–58%) also reported that they purchased meat, egg, or dairy products with the "Humane Certified" certification and 42% (CI 36–47%) reported they purchased meat, egg, or dairy products with the "American Humane Certified" certification.

To identify the extent to which consumers who buy third-party certifications also buy not-certified labels with the intention of purchasing a higher welfare product, we calculated the proportion of respondents who reported purchasing a certified product who likewise purchased a label because they thought that label indicated college-welfare product practices. Of those who reported that they purchased meat, eggs, or dairy products with one of the four certifications that specify fauna welfare (Certified Humane, Animate being Welfare Canonical, Brute Welfare Certified (GAP), American Humane Certified), upward to 59% (CI 54–64%) reported too purchasing a non-certified label considering they thought it indicated humane treatment and up to 58% (CI 53–62%) reported paying more than for a non-certified label because they idea information technology indicated college-welfare production practices (Table 4).

Give-and-take

Our results show that 86% of surveyed consumers reported purchasing at to the lowest degree one product with a welfare-related label in the past 12 months, 89% of those reported doing so because they believed the label indicated better than standard creature welfare, and 78% paid more than for the characterization because they idea the characterization indicated higher-welfare production practices. In addition, a majority of respondents who reported purchasing one of the four animal welfare-related certifications likewise purchased products with non-certified labels bold those labels indicated improved animal welfare. For example, we establish that of consumers who reported purchasing animal welfare certified products, 59% also reported purchasing the "natural" label because they believed information technology represented improved animal welfare standards. These findings advise that consumers are largely unaware of the differing affect betwixt certifications and these welfare-related labels.

These findings are consistent with several studies that demonstrate consumers incorrectly associate many labels with improved animal welfare, and that consumers seek out and pay more for these labels, even when these labels may not stand for higher-welfare production practices (Abrams et al. 2010; Dominick et al. 2017; Malone & Lusk 2016; Ochs et al. 2019). Despite the fact that the "natural" claim does not address production practices for ASF, lx% of consumers associated the "natural" merits with "improved animal handling/animal welfare practices" (Dominick et al. 2017). Consumer perceptions of labels and the production practices they stand for are oftentimes inaccurate; only 5.6% of respondents accurately understood the touch of free-range systems on hen health and stress compared with conventional systems and, similarly, merely half-dozen.nine% accurately understood the impact of cage-free (Ochs et al. 2019).

Consumers are motivated to seek out and pay more than for improved animal welfare and must rely upon labels to provide additional information about the conditions in which animals are raised to achieve their goals (Alonso et al. 2020; Janssen et al. 2016; Napolitano 2008; Spain et al. 2018). For voluntary labels to finer serve the market place for improved brute welfare practices, consumers need to be able to distinguish the animal welfare benefits associated with a given label (Sullivan 2013a; Sunstein 2016). Additionally, this lack of measurable characteristics does not facilitate comparison between products. Equally a result, consumers' estimation of process labels is left to be influenced by their beliefs, which opens the door to misunderstanding or misattributing improved welfare (Messer et al. 2017).

Our findings provide prove that consumers cannot differentiate between labels that indicate higher-welfare product practices from those that don't, suggesting that voluntary labels are not effectively communicating improvements in brute welfare to consumers. Because consumers cannot brand this distinction, they may seek out and pay more for an aspect (such as improved animal welfare) that is non present, ultimately decreasing consumer welfare and undermining the market for creature welfare (Sunstein 2016).

These data asymmetries too impact the market overall, equally they can crusade consumer mistrust in labels ultimately leading to market place failure (Akerlof 1970). ASF producers take little incentive to exceed the minimum standard required to utilize these labels when they tin can receive a price premium without modifying their product practices (Baksi et al. 2017; Darby & Karni 1973). When producers can use a label and charge a price premium without adhering to whatever different standards, there is no incentive to prefer different practices, penalizing those who are increasing their costs past shifting product practices to amend animal welfare (Akerlof 1970; Kehlbacher 2012). To incentivize producers to adopt humane practices and to enable consumers to brand informed decisions surrounding humane ASF purchases, labels need to reliably communicate accurate information well-nigh humane production practices to consumers (Harvey & Hubbard 2013; Sullivan 2013a; Sunstein 2016).

Government oversight and labels regulation could facilitate clear definitions of standards required to apply a specific characterization, which could better the communication of animal welfare benefits that a label represents to consumers (Messer et al. 2017). Studies have shown that both producers and consumers are in favor of mandatory regulation of labels through government oversight (Lusk 2019; Roe & Sheldon 2007; Wolf et al. 2016). Our results also show strong support for government regulation of beast welfare labels; 85% of respondents of our survey thought that the government should be setting and enforcing clear definitions for food labels related to animate being welfare.

Including boosted information or detail about production practices on labels may also alleviate consumer confusion, however, boosted information may cause other bug. Research has shown that excessive information may cause overload, and crowd out other of import information (such as nutritional facts) which could negatively impact consumer welfare (Lusk & Marette 2012). I possible solution may be to apply applied science to make additional information available to those consumers who desire it (Messer et al. 2017) which recommends the use of Quick Response (QR) codes on labels. This approach could make information about animal welfare standards available to consumers who desire it, without adding it straight to the packaging or label. Thus consumers will exist able to admission accurate, reliable data about animate being welfare standards and select products accordingly (Messer et al. 2017).

Limitations

1 limitation of this study is that consumers may non call back details of purchases over a 12-calendar month period, including the reasoning backside those purchases or if they paid more. For example, the proportion of individuals who reported they paid more for grass-fed pork because they thought the label indicated higher-welfare production practices was higher than the proportion who reported purchasing it because they thought the characterization indicated college-welfare production practices. Presumably, those who paid more for a label for its creature welfare benefits also purchased that label because of its animal welfare benefits. Some certification labels contain the same terms that are used in the subset of labels studied. The terms "humane", "grass-fed" and "organic" are all used in both certifications also as labels, and, every bit a event, consumers could have been confused most whether they purchased the certifications or the labels with these terms. Additionally, respondents could be more than probable to over-study purchases and the drivers behind those purchases if they perceive that response to exist more than favorably looked upon (Edwards 1990).

We also did not explore the level of quality of welfare improvement that motivated the purchase, but that consumers were motivated to buy considering they believed the label indicated higher-welfare production practices. Nor did we capture the premium consumers are willing to pay for welfare-related labels. It would be helpful for future research to quantify the specific amount consumers pay over conventional prices for welfare-related labels because they believe the label indicates improved animal welfare standards.

Conclusion

While a substantial proportion of consumers who written report purchasing these labels practice so because they believe they indicate higher-welfare production practices, these labels frequently do not have fix standards for production practices that improve animal welfare. This finding demonstrates that labels do not provide sufficient information to consumers to enable them to purchase products that align with their preferences for higher welfare ASF products. Our recommendation would be for federal regulations that set clear and specific standards for utilise of welfare-related labels, like to the standard framework used by fauna welfare certifications. Additionally, we would recommend that enforcement of these standards be accomplished through on-farm audits, either provided by the USDA or a tertiary party. These provisions would ensure that improvements to product practices would exist consistent and comparable, improving consumers' ability to compare products and purchase in line with their preferences. This change would as well serve to incentivize and reward producers who employ production practices that improve beast welfare, thus benefiting the overall market for brute welfare.

References

-

Abrams, G.M., C.A. Meyers, and T.A. Irani. 2010. Naturally confused: Consumers' perceptions of all-natural and organic pork products. Agriculture and Human Values 27 (3): 365–374. https://doi.org/x.1007/s10460-009-9234-5.

-

Akerlof, George A. 1970. "The Market for Lemons: Qualitative Dubiousness and the Market Mechanism". Quarterly Journal of Economics 84 (3): 488–500.

-

Alonso, Thousand.E., J.R. González-Montaña, and J.M. Lomillos. 2020. Consumers' concerns and perceptions of farm animal welfare. Animals 10 (3): i–13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10030385.

-

Baksi, Due south., P. Bose, and D. Xiang. 2017. Acceptance Appurtenances, Misleading Labels, and Quality Differentiation. Ecology and Resource Economics 68 (2): 377–396. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-016-0024-4.

-

Bauman, D.Due east., and R.J. Collier. 2014. Update on human wellness concerns of recombinant bovine somatotropin apply in dairy cows. Periodical of Beast Science four: 1800–1807. https://doi.org/10.2527/jas.2013-7383.

-

Brunberg, E.I., T. Bas Rodenburg, L. Rydhmer, J.B. Kjaer, P. Jensen, and L.J. Keeling. 2016. Omnivores going astray: A review and new synthesis of abnormal behavior in pigs and laying hens. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 3 (JUL): one–15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2016.00057.

-

Cusimano, C. 2008. RBST, It Does a Torso Good: RBST Labeling and the Federal Denial of Consumers' Right to Know. Santa Clara Fifty. Rev., 48, 1095.

-

Darby, M.R., and Eastward. Karni. 1973. Complimentary Competition and the Optimal Amount of Fraud Writer ( south ): Michael R . Darby and Edi Karni Published by : The University of Chicago Press for The Booth School of Business , University of Chicago and The University of Chicago Police School Stable URL : ht. The Periodical of Police and Economics Economics 16 (one): 67–88.

-

Dominick, S.R., C. Fullerton, N.J.O. Widmar, and H. Wang. 2017. Consumer Associations with the "All Natural" Food Label. Periodical of Food Products Marketing 24 (3): 249–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/10454446.2017.1285262.

-

Edwards, A. 50. 1990. Construct validity and social desirability. American Psychologist45 (two): 287–289. https://doi.org/ten.1037/0003-066X.45.2.287.

-

FDA. 1994. Food and Drug Administration. Acting guidance on the voluntary labeling of milk and milk products from cows that have not been treated with recombinant bovine somatotropin. Federal Register 59(28): 6279–6280.

-

FSIS - USDA. 2019. Food condom and inspection service labeling guideline on documentation needed to substantiate creature raising claims for label submissions. December 2019, p. ane–18. https://www.fsis.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media_file/2021-02/RaisingClaims.pdf

-

Grandin, T. 2016. Evaluation of the welfare of cattle housed in outdoor feedlot pens. Veterinary and Animal Science ane–2 (October): 23–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vas.2016.11.001.

-

Harper, Thou.C., and A. Makatouni. 2002. Consumer perception of organic food product and farm beast welfare. British Food Journal 104: 287–299. https://doi.org/ten.1108/00070700210425723.

-

Hartcher, K.Grand., and B. Jones. 2017. The welfare of layer hens in cage and muzzle-complimentary housing systems. World's Poultry Science Journal 73 (4): 767–781. https://doi.org/ten.1017/S0043933917000812.

-

Harvey, D., and C. Hubbard. 2013. Reconsidering the political economy of farm brute welfare: An anatomy of market failure. Food Policy 38 (one): 105–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2012.11.006.

-

Heng, Y., H.H. Peterson, and X. Li. 2016. Consumer Responses to Multiple and Superfluous Labels in the Case of Eggs. Journal of Food Distribution Inquiry 47 (2): 62–82.

-

Hepting, D.H., J. Jaffe, and T. Maciag. 2014. Operationalizing Ideals in Food Choice Decisions. Periodical of Agricultural and Ecology Ideals 27: 453–469. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10806-013-9473-eight.

-

Hernandez-Mendo, O., M.A.G. Von Keyserlingk, D.K. Veira, and D.Thousand. Weary. 2007. Effects of Pasture on Lameness in Dairy Cows. Journal of Dairy Science ninety (three): 1209–1214. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(07)71608-9.

-

Herring, J. L., Martin, J. 1000., Hudson, Thou. D., Nalley, Fifty. 50., & Rogers, R. Due west. 2007. Consumer Credence of "Farm Raised" Precooked Roast Beef. Journal of food quality 30 (3): 403–412.

-

Holger, S., F. Albersmeier, and J. Gawron. 2008. Heterogeneity in the Evaluation of Quality Assurance Systems: The International Food Standard (IFS) in European Agribusiness. International Nutrient and Agribusiness Direction Review 11 (3): 99–139.

-

Iannetti, 50., Romagnoli, Due south., Cotturone, G., & Vulpiani, K. P. (2021). Animal Welfare Assessment in Antibody-Free and Conventional Broiler Chicken. Animals, one–11. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11102822

-

Janssen, M., M. Rödiger, and U. Hamm. 2016. Labels for Beast Husbandry Systems Meet Consumer Preferences: Results from a Meta-analysis of Consumer Studies. Periodical of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics 29 (6): 1071–1100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10806-016-9647-two.

-

Karavolias, J., Thousand.J. Salois, K.T. Baker, and K. Watkins. 2017. Raised without antibiotics : Impact on animal welfare and implications for food policy. Journal of Animal Science one: 337–348. https://doi.org/10.1093/tas/txy016.

-

Kehlbacher, A. 2012. Measuring the consumer benefits of improving farm animal welfare to inform welfare labelling. Nutrient Policy 37: 627–633.

-

Kuchler, F., M. Bowman, M. Sweitzer, and C. Greene. 2020. Evidence from Retail Nutrient Markets That Consumers Are Dislocated by Natural and Organic Food Labels. Journal of Consumer Policy 43 (2): 379–395. https://doi.org/x.1007/s10603-018-9396-ten.

-

Ludwiczak, A., Due east. Skrzypczak, J. Składanowska-Baryza, M. Stanisz, P. Ślósarz, and P. Racewicz. 2021. How housing conditions make up one's mind the welfare of pigs. Animals 11 (12): 1–16. https://doi.org/x.3390/ani11123484.

-

Lusk, J.50. 2019. Consumer perceptions of good for you and natural food labels. A Report Prepared for the Corn Refiners Association.

-

Lusk, Jayson L. 2018. Consumer preferences for and beliefs nearly slow growth chicken. Poultry Science 97 (12): 4159–4166. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps/pey301.

-

Lusk, Jayson L., & Marette, South. (2012). No Can Labeling and Information Policies Harm Consumers? Journal of Agricultural & Nutrient Industrial Organization, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1515/1542-0485.1373

-

Malone, T., and J.L. Lusk. 2016. Putting the Chicken before the Egg Price : An Ex Mail Analysis of California ' due south Bombardment Cage Ban. Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economic science 41 (3): 518–532. https://doi.org/ten.22004/ag.econ.246252.

-

Messer, G.D., M. Costanigro, and H.M. Kaiser. 2017. Labeling nutrient processes: The adept, the bad and the ugly. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy 39 (3): 407–427. https://doi.org/ten.1093/aepp/ppx028.

-

Napolitano, F. 2008. Upshot of Information About Animals Welfare on Consumer Willingness to Pay for Yogurt. Periodical of Dairy Science 91: 910–917.

-

Norwood, F.B., and J.L. Lusk. 2011. A calibrated auction-conjoint valuation method : Valuing pork and eggs produced under differing beast welfare conditions. Periodical of Environmental Economics and Management 62 (1): fourscore–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2011.04.001.

-

Ochs, D., C.A. Wolf, N.O. Widmar, C. Bir, and J. Lai. 2019. Hen housing arrangement information effects on U. S. Egg Demand. Food Policy 87 (May).

-

Ortega, D.L., and C.A. Wolf. 2018. Demand for subcontract animal welfare and producer implications: Results from a field experiment in Michigan. Nutrient Policy 74 (Nov 2017): 74–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2017.eleven.006.

-

Pietrosemoli, Southward., and C. Tang. 2020. Animal Welfare and Production Challenges Associated with Pasture Pig Systems : A Review. Agriculture 10: ane–34.

-

Prickett, R.W., F.B. Norwood, and J.50. Lusk. 2010. Consumer preferences for farm animal welfare: Results from a telephone survey of US households. Animal Welfare 19 (3): 335–347.

-

Roe, B., and I. Sheldon. 2007. Credence expert labeling: The efficiency and distributional implications of several policy approaches. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 89 (4): 1020–1033. https://doi.org/x.1111/j.1467-8276.2007.01024.x.

-

Shields, S., & Greger, G. (2013). Animal Welfare and Food Prophylactic Aspects of Circumscribed Broiler Chickens to Cages. Animals, 386–400. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani3020386

-

Vocalizer, R.S., L.J. Porter, D.U. Thomson, G. Cuff, A. Beaudoin, and J.Thou. Wishnie. 2019. Raising Animals Without Antibiotics: U.S. Producer and Veterinarian Experiences and Opinions. Frontiers in Veterinary Scientific discipline 6 (December): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2019.00452.

-

Spain, C.5., D. Freund, H. Mohan-Gibbons, R.G. Meadow, and L. Beacham. 2018. Are they buying information technology? U.s. consumers' changing attitudes toward more humanely raised meat, eggs, and dairy. Animals 8 (viii): ane–fourteen. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani8080128.

-

Sullivan, Southward.P. 2013. Empowering Market Regulation of Agronomical Animal Welfare through Production Labeling. Animal Police force Review 19: 391–422.

-

Sunstein, C. R. 2017. On mandatory labeling, with special reference to genetically modified foods. University of Pennsylvania Police Review 165 (5): 1043–1095. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26600616

-

USDA. 2015. Meat and Poultry Labeling Terms. https://www.fsis.usda.gov/food-safety/safe-food-handling-and-preparation/food-condom-nuts/meat-and-poultry-labeling-terms. Retrieved May 2022.

-

USDA. 2000. Usa Department of Agronomics. National organic programme; final dominion. seven CFR part 205. Federal Register, December 21.

-

USDA Agricultural Marketing Services. 2013. Organic Livestock Requirements. https://www.ams.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media/Organic%20Livestock%20Requirements.pdf

-

USDA Agricultural Marketing Services. 2017. Organic livestock and poultry practices final dominion, Questions and Answers- January 2017. https://www.ams.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media/OLPPExternalQA.pdf

-

USDA Agricultural Marketing Services. 2018. Shell Egg Labeling guidelines for product bearing the USDA grademark. Mandatory Labeling Requirement. https://www.ams.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media/ShellEggLabelingUSDAGrademarkedProduct.pdf

-

USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service. 2019. Food Safety and Inspection Service Labeling Guideline on Documentation Needed To Substantiate Animate being Raising Claims for Label Submission. Federal Register, 84(248), 71359

-

Wolf, C.A., Chiliad.T. Tonsor, 1000.One thousand.S. McKendree, D.U. Thomson, and J.C. Swanson. 2016. Public and farmer perceptions of dairy cattle welfare in the United States. Journal of Dairy Science 99 (seven): 5892–5903. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2015-10619.

-

Yang, R., Raper, Grand. C., & Lusk, J. Fifty. 2017. The affect of hormone utilize perception on consumer meat preference (No. 1377-2016-109843).

Acknowledgements

A special thanks to Maya Gupta, the Senior Director of Research at the ASPCA, for editing.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-for-profit sectors.

Writer data

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Melissa Thibault: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—Original Draft, Project administration Sharon Pailler: Information Curation, Formal analysis, Validation, Methodology, Writing—Original Typhoon, Visualization Daisy Freund: Conceptualization, Writing—Review & Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ideals approval

The Advarra IRB determined that this research project was exempt from IRB oversight under the Department of Health and Human Services regulations found at 45 CFR 46.104(d)(ii)- (Pro00041227).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Non applicative.

Declarations of interest

On behalf of all authors, the respective writer states that in that location is no conflict of interest.

Boosted information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

Rights and permissions

Open up Access This article is licensed nether a Artistic Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits employ, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, every bit long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article'southward Artistic Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, y'all will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Reprints and Permissions

Most this article

Cite this article

Thibault, M., Pailler, Due south. & Freund, D. Why Are They Buying It?: The states Consumers' Intentions When Purchasing Meat, Eggs, and Dairy With Welfare-related Labels. Nutrient ideals 7, 12 (2022). https://doi.org/x.1007/s41055-022-00105-three

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s41055-022-00105-3

Keywords

- Nutrient labels

- Animate being welfare

- Consumer welfare

- Imperfect data

- Welfare certifications

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s41055-022-00105-3

Posted by: davisvien1961.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Are Modern Us Veal Processors Doing To Improve Consumer Perception Of Animal Welfare"

Post a Comment